| Graduation Year | Class of 1951 |

| Date of Passing | Sep 08, 2014 |

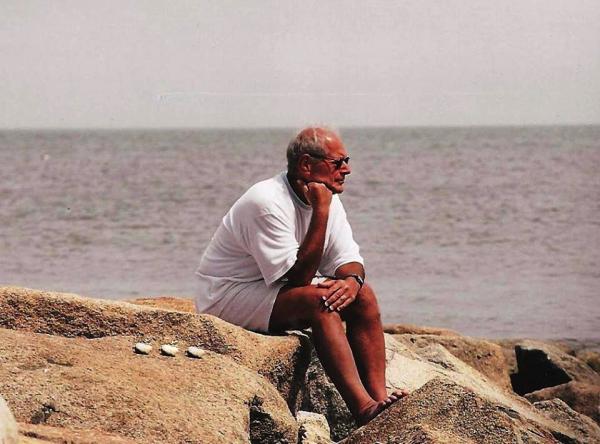

| About | Michael D. Robbins, Trusted NYSE Trader for 45 Years, Dies at 80 By Laurence Arnold 2014-09-14T23:31:01Z Robbins, a trusted New York Stock Exchange trader for 45 years, has died at the age of 80 • First Person: Trading the Day JFK Was Killed Michael D. Robbins, who combined a gregarious nature with ironclad discretion to become a prominent floor trader at the New York Stock Exchange and champion of its history and traditions, has died. He was 80. He died on the evening of Sept. 13 at his home in Manhattan, said his daughter, Jil Robbins Pollock. “He died at 7:18, which happened to be his number on the stock exchange floor,” she said. The cause was a brain tumor. During 45 years as a member of the NYSE, Robbins was a walking encyclopedia of names and numbers and redefined the role of the independent floor broker. He won the trust, and the business, of major clients such as Fidelity Management & Research Co., Putnam Investments Inc. and General Electric Investment Corp., which began turning to him, rather than Wall Street’s big-name firms, with trades they needed done efficiently and quietly. Backed by his mutual-fund clientele, Robbins won election to three terms on the stock exchange’s governing board, from 1992 to 1998. “He’s one of the most beloved figures on Wall Street,” Christopher “Goose” Henderson, Robbins’ partner for 11 years, said in a May interview. “Everybody referred to Mike as ‘the feel-good movie of the summer,’ because he was always kind and considerate. He’d remember people’s names and have knowledge of the school they went to, or the place they used to work, or who their bosses were. He made people feel warm and welcome.” Robbins retired in 2007. Since 2011 he was a contributor to Bloomberg News, providing historical perspective on market and finance news. Floor Routine Wearing that badge number 718, Robbins patrolled the stock exchange floor, covering as many as seven miles a day in the era before computerized trading. Back then, orders were received in phone booths ringing the trading floor. Their clients’ wishes in hand, traders would head out to buy and sell shares at the dozens of posts where specialists oversaw individual stocks. “The floor was like a tribal village -- that’s what I liked about it,” he told Bloomberg Radio in 2012. “It had a limited number of people: There were the insiders, there were the outsiders, there were those who knew the territory, there were those who knew the mores of it, and I wanted to be inside. And I got inside.” Henderson, who became Robbins’ partner in 1994, said they put such a high value on secrecy that they wouldn’t mention the names of their dozen A-list clients, even when on the telephone with each other. Code Words “We referred to them by numbers to protect their anonymity on the floor, because that’s what they craved more than anything,” Henderson recalled. “They wanted to hide their intentions because Wall Street had started to get in bed with the predatory hedge funds” -- those that sought to profit off the trading intentions of others. A. Peter Low, another four-decade veteran of the NYSE who became a managing director at Griswold Co., wrote in 2006 that Robbins “became the architect of an elite and well-respected floor-based business catering to investment advisers as well as to corporations involved in share repurchase programs.” Like any agent of change, Robbins met resistance. In 1986, he took on the NYSE establishment by fighting for the right, as an independent broker, to use a telephone on the trading floor, a privilege then reserved for member firms. SEC Decision He joined William J. Higgins, whose application to use a portable telephone on the floor had been denied, in appealing the NYSE board decision to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC sided with Higgins and Robbins, a step toward opening up the once-closed club. On what became known as Black Monday -- Oct. 19, 1987, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 508 points, or 22.6 percent -- Robbins devoted his day to his client Fidelity, then the largest U.S. fund company by assets, which was inundated by clients wanting to cash out of stocks. He said he sold 2 million shares of General Electric that day to help Fidelity free up cash. “I spent all my time shoveling out GE as fast as buyers would come in,” he recalled. Fidelity later acknowledged that it was the mutual fund group singled out (not by name) in the report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms -- which investigated the causes of the crash -- for selling about $500 million in the first hour of trading and being a major part of what “overwhelmed the stock market at the opening.” Boston-based Fidelity said it made adjustments following Black Monday to respond better to surges in shareholder redemptions. Quoting Shakespeare Robbins’s twin passions for business and opera –- he was a Metropolitan Opera subscriber from 1956 –- met on his Bloomberg message screen, which he personalized with a quote from Act 3 of “The Merchant of Venice:” “Now, what news on the Rialto?” Loosely translated to modern-day conversation, that means, “So, how’s the market doing today?” Michael David Robbins was born on Sept. 19, 1933, and raised in Yonkers, New York, one of two boys of Joseph Robbins, a pharmacist, and the former Laura Neufeld. His father’s pharmacy was a meeting place for doctors, who would congregate between house calls in a lounge area, share drinks and talk stocks. Robbins’ parents caught the equity bug. Throughout the 1930s, whenever they had extra money, they would buy shares of companies they knew firsthand -- Pepsi-Cola Co. (PEP), Procter & Gamble Co., Pfizer Inc., American Home Products Corp. Stock Holdings “When my father died in 1974, we opened up the safe deposit box and we found tens of thousands of shares of all the consumer-related stocks: Norwich Pharmaceutical, which made Pepto-Bismol, the Plough company -- Abe Plough’s company, which made St. Joseph’s Aspirin -- and it worked. So I was imbued with it. The eighths and quarters started dancing through my veins very early on.” While at Princeton, Robbins spent the summer of 1952 on Wall Street as a runner for Clark Dodge & Co., delivering stock certificates and certified checks in a leather pouch. The job was mainly filled by retired police and firemen, except for “a few lucky summer kids -- ‘student princes,’ as they were known at Clark Dodge.” Most of the 804 men in Princeton’s class of 1955 headed to medical school, law school or some other graduate studies, Robbins recalled, while he and just two others headed for Wall Street. He saved a letter that his mother sent him at that time, reminding him of the lesson the family had lived: “The path to wealth is through common stocks.” Client Introduction He began work at Eastman, Dillon, Union Securities & Co., across from the stock exchange at 15 Broad St., at an annual salary of $3,000. Disque Deane, the financier and real-estate investor, became a mentor, accompanying Robbins on his first visit to an institutional client, the Sears Roebuck pension plan in Skokie, Illinois. Robbins proved a quick study. In 1959, he raked in $100,000, earning a gold belt buckle from the firm. That year he married Lois Otten, whose father, Louis Otten, was a New York State Family Court judge. In 1962, Robbins spent $132,500 –- some of it borrowed from his parents –- for a seat on the NYSE. “Average daily volume that year was 3,818,000 shares, a mini-thimble compared to today,” he wrote in 2012. “Total shares traded by me the first day were 400: 200 shares of Dow Chemical and 200 shares of Best & Co. It was also the first (and last) time I had a two-martini lunch.” Career Turn In 1978, following four years as a partner at Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette, Robbins left to become a specialist, or a floor trader in charge of making markets in certain stocks. It was, by his admission, not a good fit, and in 1980 he set off to start his one-man independent brokerage. In 1992, the NYSE nominating committee chose Robbins among six new directors for its governing board. He served three two-year terms as a representative of the securities industry. He also served as an NYSE floor official and floor governor and led the Alliance of Floor Brokers for more than 10 years. In 1994 he was joined by Henderson, a partner at the specialist firm Henderson Brothers Inc., at what became Robbins & Henderson LLC. The firm had gross revenue in 2006 of $6.4 million, according to a 2007 news release announcing its acquisition by Van der Moolen Holding NV. Client Communication That ended Robbins’ 55 years on Wall Street. In a farewell letter to his clients, he wrote: “At the NYSE, 75 is not old, it is ancient. I am aged wood but still young enough, between the ears, to give years of trouble-free service. I have always considered myself a condiment rather than an ingredient: applied at the discretion of the consumer, not the preparer. Please keep me on your spice shelf.” Robbins was on the board of Princeton AlumniCorps, also known as Project 55, an initiative formed by Princeton’s class of ’55 to place graduates in fellowships and internships with organizations that address societal needs. He also served as a trustee of the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library & Museum in Staunton, Virginia, and a board member of Friends of the Princeton University Library. In addition to his wife and daughter, survivors include two other daughters, Juli Greenwald and Polly White; a brother, Benedict Robbins; and six grandchildren. To contact the reporter on this story: Laurence Arnold in Washington at larnold4@bloomberg.net To contact the editors responsible for this story: Charles W. Stevens at cstevens@bloomberg.net Steven Gittelson |